By Danielle MacDowell

Main Takeaways

- Our body is composed of two nervous systems, the central nervous system (CNS) and the enteric nervous system (ENS).

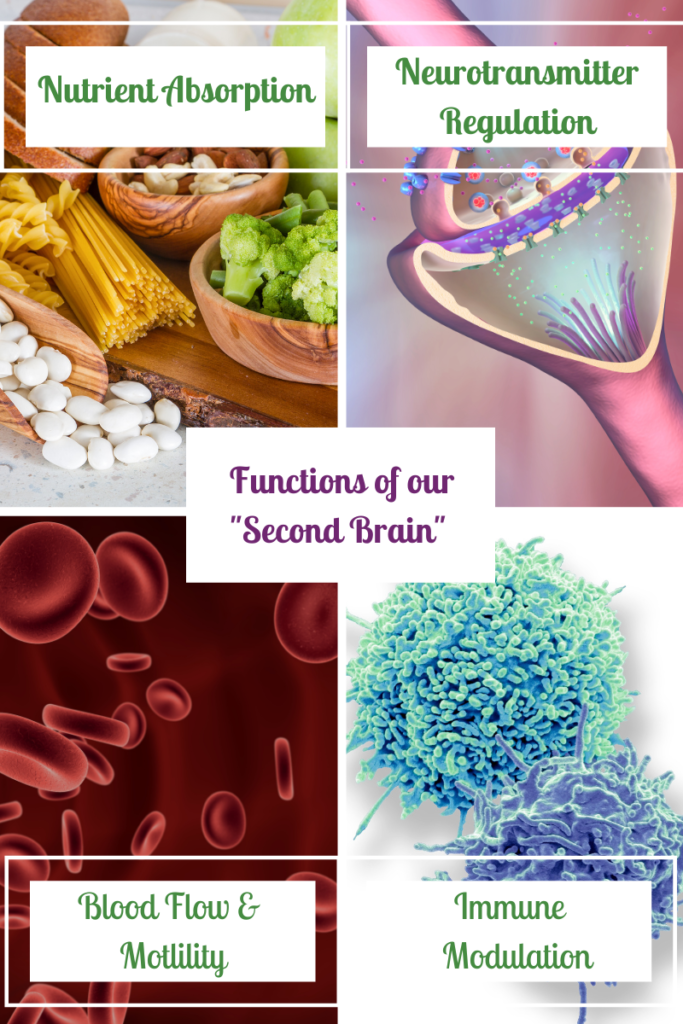

- The enteric nervous system controls the functions that occur in our gut. It is sometimes referred to as our “second brain.”

- The ENS controls tissue secretion, nutrient absorption, immune functioning, hormone production, the intestinal barrier, microbial community, and secretion of neurotransmitters.

- The communication between the ENS and the CNS happens via the vagus nerve.

- The microbes in our gut microbiome are also suspected to play a role in our gut-brain signaling.

- Gut microbes influence the vagal nerve and intestinal barrier health, which in turn, may impact our mental health.

- There is a subset of probiotics, known as psychobiotics, that may also be advantageous to mental health.

- Probiotics have been shown to significantly reduce symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress in healthy individuals.

- More research needs to be done to determine the extent in which probiotics can impact the mental health of individuals with comorbid conditions.

Table of Contents

Have you ever wondered why you feel “butterflies in your stomach” when you are excited? Or why you feel a “pit” in your stomach when you are nervous? Well, you are not alone in questioning these reactions.

It turns out there is actually a logical explanation for your body’s response to emotional stimuli, such as excitement and nervousness. Believe it or not, we have two nervous systems in our body, the central nervous system, which is our body’s primary command center, and the enteric nervous system, which is the control center for the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

In order for the body to function properly, these two nervous systems communicate regularly with one another via the vagus nerve. This “communication” is essentially what you are experiencing when you get a “gut feeling.”

One Body: Two Nervous Systems

When you think about the nervous system, what comes to mind? If you are like most people, you are likely thinking about the brain, the spinal cord, and the nerves. While this thought process is not incorrect, what most people do not realize is that our body is actually composed of two nervous systems, the central nervous system (CNS) and the enteric nervous system (ENS).

Our more well-known nervous system, the CNS, encompasses the brain, the spinal cord, and most of the body’s nerves; this is our body’s main command center. It controls functions, such as our movements, our reactions, our emotions, our sleep-wake cycle, our hormones, our balance, the list goes on…

The nervous system found in our digestive tract is known as the enteric nervous system (ENS) and it controls the functions that occur in our gut. It is sometimes referred to as our “second brain.”

Our Second Brain

As mentioned above, the gastrointestinal tract has its own neural network, which is known as the ENS. It contains a whopping 100-500 million neurons! [1] Considering that the digestive system houses 70% of our immune system, provides a protective barrier for our bloodstream, and is responsible for digesting and absorbing all of our life-giving nutrients, amongst other functions, there is certainly a good reason behind all of this neural activity.

As you are probably realizing by now, in spite of popular belief, the brain is not at the epicenter of all functions of our body. While many of the functions of the digestive system are controlled by both the ENS and the CNS, the ENS is actually semi-autonomous, as it independently controls functions, such as local blood flow and motility. [2] However, the functionality of the ENS doesn’t stop here.

The ENS regulates a number of additional functions in the GI tract, which have been identified by Nezami & Srinivasan [3] and include:

- Tissue secretion (e.g. mucus secretion, which is needed for protective barrier and immune defense)

- Nutrient absorption

- Immune functioning

- Hormone production

- Intestinal barrier

- GI microbiota community

- Neurotransmitter secretion [3]

Gut-Brain Axis: Bidirectional Cross-Talk Between Gut and Brain

Contrary to what was once believed, the communication pathway between the brain and the GI tract is not a one-way street from the brain to the gut. This two-way communication between these two important organs is known as bidirectional crosstalk, also known as the gut-brain axis (GBA).

The communication between the ENS and the CNS happens through a very important nerve, the vagus nerve. The vagus travels from the gut to the brain. Similar to the way a telephone wire transmits signals from one phone to another, the vagus nerve transmits signals between the gut and the brain.

Optimal functioning throughout the body is dependent upon the ongoing communication between these two nervous systems. Because of their tight interconnection, dysfunction in one organ can trickle down to the other organ. A clear example of this intricate relationship is the connection between stress and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

The Gut Microbiome’s Influence on Gut-Brain-Communication

While the vagus nerve serves as the communication conduit between the gut and the brain, there are many influential factors that contribute to the signals that the vagus nerve transmits, including hormones and peptides. The microbes in our gut microbiome are also suspected to play a role in our gut-brain signaling. This may be due to their influence on the vagal nerve or due to their role in intestinal barrier health.

One of the most important functions of the microbes in our gut is to maintain a hardy intestinal lining. This lining is known as our gut barrier. When this barrier is degraded, as in the case of intestinal permeability, foreign particles, such as undigested food, pathogens, and bacterial metabolites can enter into our bloodstream. Some of these foreign invaders can also cross the blood brain barrier (BBB), which can cause inflammation. When coupled with other risk factors, this resulting neurological inflammation can then set the stage for mental health conditions, such as depression. [4]

While we understand potential mechanisms for how the gut microbiome can affect our neurological functioning, there is still more to uncover. That being said, it is becoming more and more evident that the health of the gut microbiome can affect the state of our brain, and in turn, our mental health. Because of this connection, more research is being devoted to probiotic therapy and mental health outcomes.

The Gut Microbome and Mental Health

The recognition that our gut and brain are interconnected is not a new idea. In the 19th and 20th centuries, progressive individuals hypothesized that illness, including mental illness, was the cause of an unhealthy or unbalanced gut. [5] As a result, some practitioners even replaced conventional treatment methodologies for probiotics to treat various illnesses. [5]

Fast forward to today. We now know that there is bi-directional communication between the gut and the brain. Remember, the brain has the capability to send communicative signals to the gut, and vice versa. So, when the gut is imbalanced, it is suspected that negative neurological consequences can result. So, it is plausible that by correcting the gut, neurological functioning will be positively impacted.

Probiotics and Mental Health

At this point you may be wondering how you can correct an imbalance in your gut. One way to do this is through the use of probiotics, via food, supplementation, or fecal microbial transplant.

Probiotics are live microorganisms that provide health benefits to its host. They are essentially the “good bugs” that reside in our GI tract and are important players in a healthy microbiome. The benefits of probiotics are well-documented; they are essential for immune functioning, barrier protection, vitamin synthesis, and digestive support. They may also play a role in mental health, especially as it relates to anxiety, depression, and stress.

In a systematic review published in 2017, [7] focusing on probiotics and mental health, researchers identified seven studies that met their specified inclusion criteria. After careful review, researchers concluded that probiotics significantly reduced “pre-clinical psychological symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress in healthy individuals”. [7]

It is important to note that these findings contrasted with an earlier systematic review conducted by Romjin and Rucklidge in 2015 [5]. This analysis included participants who smoked and who had comorbid conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. While, the research conducted by McKean et al. [7] reveal that probiotics can have a significant impact on healthy individuals suffering from anxiety, depression, or stress, research conducted by Romjini and Rucklidge [5] show that individuals who smoke and/or have an inflammatory disease may not experience the same symptom relief.

It is important to note that dosage, probiotic strain, and duration of use influence outcomes. So, if you are someone with a comorbid condition, try not to get discouraged with the above results. It is plausible that probiotics may still be beneficial. It may simply be that the research has not yet revealed the correct strain, dosage, or duration needed for the specified conditions. Fortunately, this research is ever-evolving and I suspect that there is more to be discovered in terms of using probiotics therapeutically.

Use Food to Bolster Your Microbiome

After all of this talk about how an impaired microbiome can impact your mental health, you may be wondering how to get the good microbes, aka probiotics, into your body. Well, there are plenty of food sources that can be used to replenish your body’s microbe stores. Whole food, fiber-rich sources are especially beneficial when striving for healthy levels of the good bacteria in your gut.

Fiber-Rich Foods: Aim for 25-30 grams a day. However, if you are not used to eating fiber, introduce fiber into your diet slowly to prevent discomfort.

Healthy sources of fiber include:

- Fruit

- Vegetables

- Beans and legumes

- Nuts

Probiotics: There are a number of ways to increase the “good” bacteria in your gut by eating probiotic-rich food, including:

- Yogurt

- Kefir

- Kombucha

- Sauerkraut

- Fermented vegetables

- Miso

Prebiotics: The role of prebiotics in gut health are just as important as probiotics. Prebiotics are essentially food sources for probiotics. Some sources include:

- Green bananas

- Artichokes

- Asparagus

- Oat bran

- Psyllium

- Raw garlic

- Onions

Fecal Microbial Transplants, C. Diff. & Autism

While food and supplements are the two most common approaches used to replenish the body’s microbial stores, I would be remiss if I did not mention a third method, fecal microbial transplants (FMT). And, yes, it is exactly what it sounds like. Fecal matter is obtained from a healthy donor and transplanted into another host to populate the gut with diverse and healthy flora.

At this point, you are likely squirming in your seat a bit at the thought of FMT….but try not to let the gross factor deter you in learning about it. It actually has demonstrated real therapeutic potential. For example, it has been used successfully to treat clostridium difficile (C. diff) infection. In experimental settings, it has also yielded some promising effects in reducing behaviors and GI issues in individuals with autism. [6]

Word of Caution: While FMT has produced some exciting results, FMT should only be used for specific medical conditions and only be performed by medical doctors.

Final Thoughts and Main Takeaways

While we understand potential mechanisms for how the gut microbiome can affect our neurological functioning, there is still more to uncover. That being said, it is becoming more and more evident that the health of the gut microbiome can affect the state of our brain, and in turn, our mental health. Probiotic supplementation has shown to be useful in alleviating symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress, in otherwise healthy individuals. More research needs to be conducted to determine if probiotics confer the same effect on individuals with comorbid conditions.

- Breit S, Kupferberg A, Rogler G, Hasler G. Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:44. Published 2018 Mar 13. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044

- Costa M, Brookes SJH, Hennig GWAnatomy and physiology of the enteric nervous systemGut 2000;47:iv15-iv19.

- Nezami BG, Srinivasan S. Enteric nervous system in the small intestine: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12(5):358-365. doi:10.1007/s11894-010-0129-9

- O’Connor JC, Lawson MA, André C, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14(5):511-522. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4002148

- Romijn AR, Rucklidge JJ. Systematic review of evidence to support the theory of psychobiotics. Nutr Rev. 2015 Oct;73(10):675-93. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuv025. Epub 2015 Sep 13. PMID: 26370263.

- Doenyas C.Gut Microbiota, Inflammation, and Probiotics on Neural Development in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuroscience. 2018 Mar 15;374:271-286. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.01.060.

- McKean J, Naug H, Nikbakht E, Amiet B, Colson N. Probiotics and Subclinical PsychologicalSymptoms in Healthy Participants:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of ALternative and Complementary Medicine. 2017, 23 (4); 249-258.